Classical Music Americana

We’ve created Spotify and YouTube playlists containing the works discussed here for your enjoyment.

This year, many of us will celebrate a very different Thanksgiving, that quintessential American holiday. It will be a smaller, quieter event. While missing the exuberance of larger gatherings, this year may offer more time for reflection, and there’s a lot to think about right now. In pondering some of the enormous questions our country must resolve, I’m starting with what is most familiar to me—classical music.

What is the history of classical music in this country? How do you define it? What traditions have contributed to it? Does it have a distinctive sound? In considering all of this, I’ve put together a playlist, recognizing that this is only a fraction of what’s out there. I have not included jazz here. That’s intentional, though jazz has been called ”America's classical music.” I’ve also left out rock and roll, considered by many around the world to be the “real” American music. Instead, I’ve limited this list to 20th century composers and works that may embody attributes some have used to describe musical Americana—expansive, open, bold, driven, sorrowful, and sometimes optimistic. This is all very subjective, but perhaps in this collection of the well known and little known, the often heard and the under-heard, we can begin a journey of understanding about what might make American classical music truly great. But it’s only the beginning.

Libby Larsen

Libby Larsen

Let’s start in the heartland, with Minnesotan Libby Larsen, who writes “Music has always been influenced by the spoken language. Italian, German, Russian and French music sounds distinctly Italian, German, Russian and French…So I begin to ask, what is the melody of American English? And can it best be expressed through strings?” Here’s a movement from her Symphony No. 4, “String Symphony,” performed by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

The next choice is obvious, for many of us. Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, written in 1944 as a ballet for Martha Graham, is a favorite American work for many.

Here’s a short Thanksgiving palate cleanser, written and performed by guitarist Andrew York, called Home.

George Walker (photo by Frank Schramm)

George Walker (photo by Frank Schramm)

And here is a beautiful, elegiac work by George Walker, the first African American graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, and the first Black man to receive a doctorate from the Eastman School of Music. In 1996 he became the first African American to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music, for his piece Lilacs. This work, Lyric for Strings, was written in 1946. Originally titled Lament, it is dedicated to his grandmother, who had been enslaved.

Florence Price (photo from Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries)

Florence Price (photo from Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries)

Next is a movement from Florence Price’s work for string quartet, Five Folksongs in Counterpoint. Price rose to fame when her prize-winning Symphony in E minor was performed by the Chicago Symphony in 1932. Several years later, mezzo-soprano Marian Anderson concluded her landmark concert from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with Price’s arrangement of My Soul's Been Anchored in the Lord. Here’s the Catalyst Quartet, performing the third movement of Price’s quartet.

Samuel Barber, a classmate of George Walker’s at the Curtis Institute, wrote his beloved Adagio for Strings in 1936, originally as the second movement of his String Quartet, Op. 11. There are hundreds of recordings of this work, but for this moment, I’ve chosen one that is especially timely—a recording of the Covid Cello Project 10, featuring 278 cellists from 29 countries.

Amy Beach

Amy Beach

Amy Beach was the first successful American woman composer. The Boston Symphony premiered her Gaelic Symphony in 1896, and it was also the first published work of music by an American woman. She was an accomplished pianist as well, and despite her husband’s demand that she restrict her public concerts and continue her composition studies without a teacher, her works received a good deal of critical acclaim in her day. She premiered her Piano Concerto as soloist, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1900.

William Grant Still

William Grant Still

An important figure of the Harlem Renaissance, William Grant Still’s first major orchestral work, Symphony No. 1 “Afro-American,” was premiered in 1931 by the Rochester Philharmonic, conducted by Howard Hanson. In addition to writing more than 200 works, including the first American opera to be performed by the New York City Opera, Still was the first African American to conduct a professional symphony in the U.S. Here is the first movement of his Symphony No. 1.

Hailing from Wahoo, Nebraska (no joke), Howard Hanson started his teaching career in California and ended up as the director of the Eastman School of Music. A winner of the Rome Prize for composition in 1921, he became a champion of American classical music, premiering 8 works by his friend and colleague, William Grant Still. His Symphony No. 2 “Romantic,” was commissioned by the Boston Symphony in 1930. He described his music as “springing from the soil of the American midwest.”

Joan Tower’s Made in America was commissioned by the unusual partnership of the American Symphony Orchestra League and the Ford Motor Company, for 65 regional U.S. orchestras. The composer writes “When I started composing this piece, the song America the Beautiful kept coming into my consciousness. This theme is challenged by other more aggressive and dissonant ideas that keep interrupting, unsettling it, but America the Beautiful keeps resurfacing in different guises…as if to say “I’m still here, ever changing, but holding my own.” A musical struggle is heard throughout the work. Perhaps it was my unconscious reacting to the challenge of “how do we make America beautiful?”

New Yorker Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson wrote classical music, as well as jazz and pop. He served as pianist in the Max Roach Quartet, and as Music Director of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. His works include scores for television and film, as well as arrangements for Motown. The third movement of his Sinfonietta No. 1, written in 1996, is dedicated to his grandson, and playfully references the folksong L’il Brown Jug. It's performed here by the Sphinx Virtuosi.

Jessie Montgomery (photo by Jiyang Chen)

Jessie Montgomery (photo by Jiyang Chen)

Jessie Montgomery only qualifies as a 20th century composer because of her birth date. In addition to composing, she is an active chamber musician (with the Catalyst String Quartet) and a music educator. Her work often focuses on language and social justice. The Washington Post describes her piece, Strum, as “Turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life…like a handful of American folk melodies tossed into a strong wind, cascading and tumbling joyfully.” So we end where we began, with the Minnesota Orchestra performing this work.

But at the end of this quick trip through the last century, Jessie Montgomery is our bridge to the 21st century, and the future of classical music in America looks bright. And we are grateful.

Wishing you a happy and healthy Thanksgiving,

Melanie Smith

President, San Francisco Performances

Franz Schubert

Franz Schubert

Dreamers’ Circus

Dreamers’ Circus

Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain (Photo: Allison Burke)

Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain (Photo: Allison Burke)

David Samuel

David Samuel

Jay Campbell

Jay Campbell

Laura Snowden

Laura Snowden

Natasha Paremski

Natasha Paremski

Richard Goode

Richard Goode

Jonathan Biss

Jonathan Biss

Timo Andres (Photo by Calla Kessler for the New York Times)

Timo Andres (Photo by Calla Kessler for the New York Times)

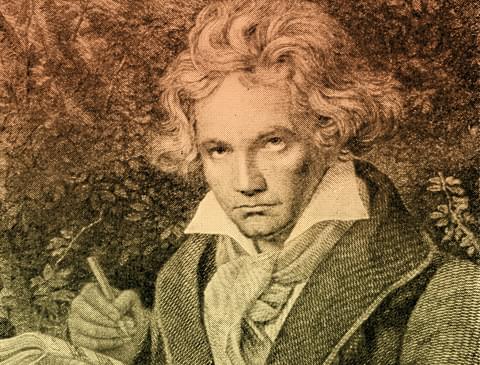

Beethoven

Beethoven

Nicholas Phan (Photo by Henry Dombey/ClubSoda Productions)

Nicholas Phan (Photo by Henry Dombey/ClubSoda Productions)

Alexander String Quartet

Alexander String Quartet

Garrick Ohlsson

Garrick Ohlsson

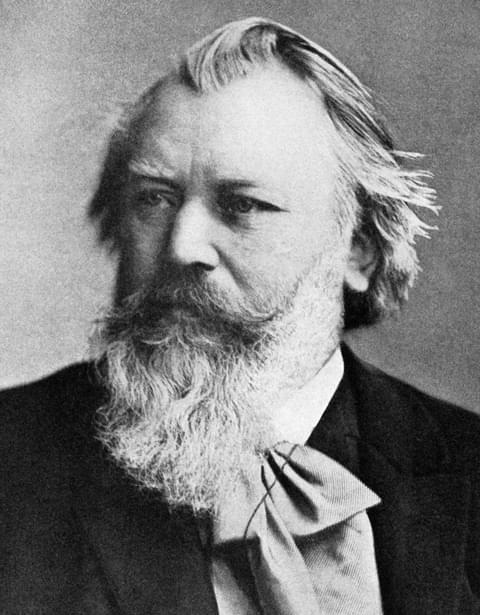

Brahms

Brahms

Sting

Sting Michael Novak (photo by Bill Wadman)

Michael Novak (photo by Bill Wadman)

Esplanade by Paul Taylor. Photo by Paul B. Goode

Esplanade by Paul Taylor. Photo by Paul B. Goode

Concertiana by Paul Taylor. Photo by Paul B. Goode

Concertiana by Paul Taylor. Photo by Paul B. Goode

Arts commentator Cy Musiker, Jennifer Koh and Vijay Iyer

Arts commentator Cy Musiker, Jennifer Koh and Vijay Iyer

Kronos Quartet

Kronos Quartet

Brooklyn Rider

Brooklyn Rider

Philip Glass

Philip Glass

Alexander String Quartet

Alexander String Quartet

Cyrus Musiker

Cyrus Musiker

Brentano String Quartet and Dawn Upshaw

Brentano String Quartet and Dawn Upshaw

Jamie Barton

Jamie Barton

Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Jay Campbell

Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Jay Campbell

Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center

Mark Rothko, No. 10 (1950) and The Metropolitan Museum

Mark Rothko, No. 10 (1950) and The Metropolitan Museum

Los Angeles Guitar Quartet

Los Angeles Guitar Quartet

Pat Metheny

Pat Metheny

Jake Heggie

Jake Heggie

Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy

Richard Goode

Richard Goode

Alexander String Quartet with Robert Greenberg

Alexander String Quartet with Robert Greenberg

Dianne Nicolini

Dianne Nicolini

Mark Padmore

Mark Padmore

Dawn Upshaw

Dawn Upshaw

Benjamin Appl

Benjamin Appl

Natasha Paremski and Alfredo Rodríguez

Natasha Paremski and Alfredo Rodríguez

Milij Aleksejevič Balakirev composed Islamey with the intent of turning it into a symphony

Milij Aleksejevič Balakirev composed Islamey with the intent of turning it into a symphony

The boat on its final summer voyage and the last of the summer peaches

The boat on its final summer voyage and the last of the summer peaches

Late summer on Clear Lake

Late summer on Clear Lake

Ruins at Ostia Antica

Ruins at Ostia Antica

Scene from Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Scene from Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government

San Fruttuoso

San Fruttuoso